- Home

- News & Events

- News

FTMC physicist Dovilė Čibiraitė-Lukenskienė develops sensors to improve understanding of processes in the stratosphere

The stratosphere is the second layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, beginning slightly above the cruising altitude of commercial aircraft and extending several times higher, through the entire ozone layer, up to around 50 km. Owing to the ozone’s ability to absorb short-wave ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, the upper stratosphere is warmer (reaching up to 0 °C), while the lower stratosphere can be as cold as -60 °C.

The stratosphere is important to all of us because it protects our skin and eyes from harmful ultraviolet radiation, contributes to the balance of radiation entering and leaving the Earth, and helps maintain the stability of the climate system. For example, sudden stratospheric warmings can alter winter weather in Europe or North America.

Even small changes in the stratosphere can have a significant impact on the Earth’s climate, which is why this region of the atmosphere is attracting increasing scientific attention. Lithuanian researchers are no exception. Dr Dovilė Čibiraitė-Lukenskienė, a physicist at the FTMC Department of Optoelectronics, is developing sensors for atmospheric gas spectroscopy – a method that uses light to reveal detailed information about the composition of air and its changes.

Fingerprints can be found in the sky too

The new sensors are designed to operate in the 2–5 terahertz (THz) frequency range. One of the key properties of this range is its sensitivity to molecular vibrations of gases – a kind of “fingerprint” unique to each substance – which can be exploited to observe climate-change-related phenomena.

“All gases have their own ‘fingerprints’, known as absorption lines at specific frequencies. The task of our sensor is to monitor this spectral absorption in order to determine which gases are present, in what quantities, and how they are distributed in the environment being studied. In the case of the stratosphere, such gases might include carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxide, or ozone,” explains the FTMC researcher.

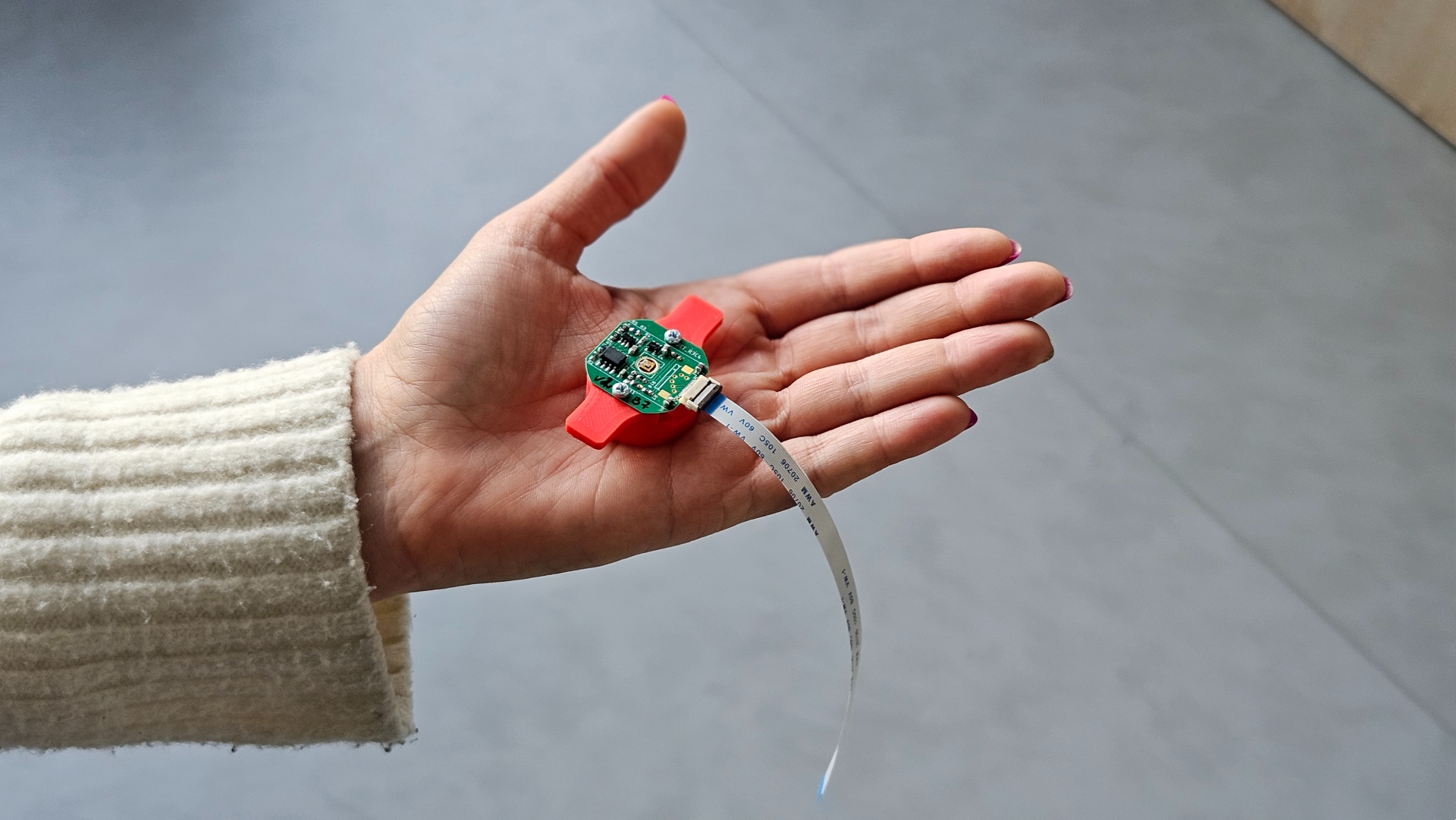

(A sensor developed by Dr Dovilė Čibiraitė-Lukenskienė. Photo: FTMC)

From bulky ‘wardrobes’ to a compact system

According to Dovilė, small sensors could help solve a huge problem in climate monitoring – quite literally.

“Current climate-change models are based on data collected from gas flows near the Earth’s surface – in the troposphere and the lower layers of the stratosphere, where these flows are relatively well studied. This is why it is now particularly interesting to investigate additional processes occurring in the stratosphere that may influence the Earth’s climate,” she says.

But how can scientific equipment reach such heights? Meteorological or scientific balloons can be used. Meteorological balloons are relatively inexpensive and can carry payloads of up to several kilograms. Scientific balloons, used by space agencies such as NASA and ESA, are significantly more expensive because they must lift much heavier scientific equipment and be adapted for specialised experiments.

“Until the end of 2022, a stratospheric research observatory called SOFIA was in operation, funded by NASA and the German Space Agency. It was a Boeing 747SP aircraft that flew at altitudes of up to 14 kilometres, carrying a 17-tonne telescope and observing atmospheric gas flows using the GREAT spectrometer, which alone weighed half a tonne.

It is hard to imagine such ‘wardrobes’ being lifted to the desired altitude – the upper stratosphere – by a balloon, and aircraft cannot fly that high either. Therefore, new methods must be developed to make measurement equipment lighter, smaller and cheaper. We hope that the sensitive optoelectronic sensors we are developing, with extended frequency ranges, will be able to replace certain components in lighter future systems,” says Dr Čibiraitė-Lukenskienė.

(SOFIA Flying Infrared Observatory. Photo: Wikipedia)

Thus, the sensor would be one crucial component of a new system, while the system as a whole is being developed jointly by scientists from different countries. Dovilė is currently collaborating with the German Space Agency, which has experience in developing the system used in the SOFIA observatory; the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom, which has produced the most powerful quantum cascade laser for this frequency range; and the Technical University of Munich, which has developed a broadband terahertz source that will be used in the creation of these sensors.

The scientific project proposed by the Lithuanian researcher, entitled “Atmosphere spectroscopy using terahertz sensors dedicated to quantum cascade laser sensing”, focuses on the development of these sensors and was recognised in 2025 as beneficial to society, receiving European Union funding for postdoctoral fellowships.

“I hope we will be able to refine our sensors as quickly as possible, and that our partners will see value in integrating them into the next generation of spectroscopic systems they are developing – systems weighing just 60 kg and capable of reaching the stratosphere using scientific balloons,” says the FTMC scientist, who will test the first prototype during a fellowship at the University of Leeds in mid-January and plans to complete the project by mid-2027.

Written by Simonas Bendžius, FTMC Public Relations and Communication Specialist.

Funded by the European Union (Project 101244503 – AtSpecTS). The views and opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. The European Union cannot be held responsible for them.